Richard Fleischner

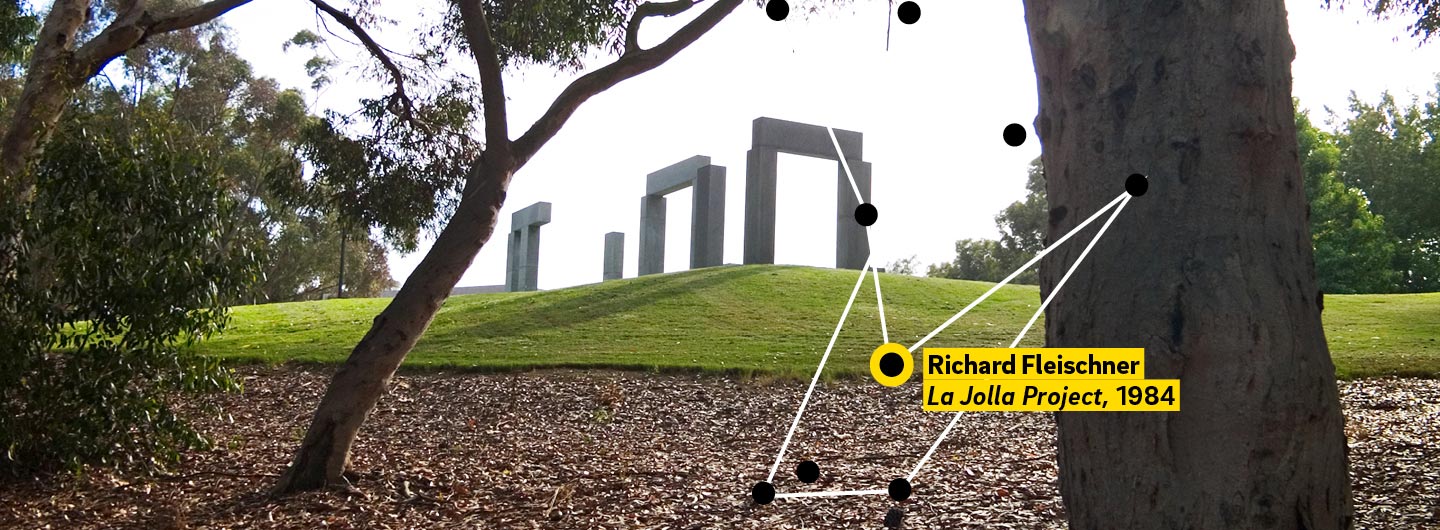

La Jolla Project (1984)

Location: Revelle College lawn, south of Galbraith Hall

Audio Tour

About the Artist

Richard Fleischner began to work environmentally in the 1970s; for him elements of nature could themselves serve as sculptural media. Fleischner has used hay, sod, grass, and wooden structures to project universal architectural forms into the ephemera and a variety of natural settings. The maze, the corridor, and the rudimentary shelter have been important sources for Fleischner, but he also draws inspiration from his knowledge of historical monumental sites. These range from Egyptian pyramids to Greek temples, where the play of architectural elements is the essence of a place.

Other important sited works include: the Balsillie School at the Center for International Governance Innovation in Waterloo, ON (2010-2012); the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge (2008-10 and 1980-85); a memorial for victims of 9/11 at the Marsh & McLennan headquarters in New York (2002-03); Brown University War Memorial (1996-97); a 3000 sq. ft. terrazzo inlay in the Cancer Center atrium at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill (1995-98); and a large outdoor park area in front of the Judicial Building in downtown St. Paul, MN (1988-91).

About the Artwork

Fleischner's La Jolla Project, completed in 1984 and the third work in the Stuart Collection, is located on the Revelle College lawn south of Galbraith Hall. Seventy-one blocks of pink and gray granite are arranged in configurations that refer to architectural vocabulary: posts, lintels, columns, arches, windows, doorways, and thresholds. Like players on a field or game pieces (Fleischner made a series of small game like sculptures in the late sixties), these elements transform an ordinary, nearly flat lawn into a space with allusions ranging from an ancient ruin to a contemporary construction site. Fleischner's work is always determined by the topography of a site, its spatial relationships, and the distinctive ways people move through and around it. What is most important for him is to interpret and essentialize a place by using minimal means to delineate natural lines and boundaries, while establishing an interplay of horizontal and vertical elements. There is no single way to experience La Jolla Project - it generates a complex set of spatial and historical relationships that invigorate and give meaning to the formerly undefined area it occupies. The stones for La Jolla Projectwere quarried in New England and cut near Providence, Rhode Island, where the artist lives and works.

Folklore

The La Jolla Project is more commonly known on campus as "Stonehenge." It is a popular place for students to go to talk or study.

Archival Images

Essay

Richard Fleischner

La Jolla Project, 1984

Place making is Richard Fleischner’s métier. He thinks about architecture in terms of environment—of how people move through space, and how that space feels. In the 1970s, he began to practice outside the studio, using hay, tufa (a sandy, porous rock), sod, and other materials as sculptural elements in mazes, corridors, and lines that redefine the territory around them. The negative, surrounding space is fully engaged in his work and as important as the objects themselves.

Faculty members in the Department of Visual Arts had recommended Richard early on, and the Stuart Collection Advisory Board liked the idea. He first visited the campus in 1982, seeking a place with “definable boundaries whose presence didn’t limit that site.” The perspectives and viewpoints he could establish in such a place, in other words, would extend beyond its boundaries.

Richard’s immediate choice was at a beautiful chaparral-filled canyon above the Scripps Institution of Oceanography, near an area of housing for married graduate students. Here a large flat area funneled toward the canyon, which dropped steeply down to the Scripps campus and then to the ocean. Another area Richard liked was a large eucalyptus grove in the northeastern quadrant of the campus, a territory set aside as a preserve in the university’s long-range plan. Rough trails pass through this dense forest area and then out to open canyons and scrub terrain. Preliminary drawings for these two sites were presented to the advisory board, which received them enthusiastically.

Subsequent examination of the university’s long-range plans revealed that the Scripps canyon area was destined to be a parking lot. Richard returned with his assistant, Lane Myer, and began developing a proposal for the eucalyptus grove, which we had permission to use. When Richard was staking out the work, however, he discovered recently dug post-holes—clearly for some structure. It turned out that exercise stations were being built here for a running course. Our investigations hadn’t revealed this because the project had been given the go-ahead ten years earlier, and was now all but forgotten by everyone except the staff of the Athletics and Recreation Department, who had finally raised the money and were going ahead without the usual bureaucratic notifications. This was early in the life of the Stuart Collection; we had much to learn.

Even so, the importance of choosing our battles wisely was always evident, and it became clear that we shouldn’t challenge this use of the site, which was, in fact, well suited for the parkour. We asked Richard, now a bit perturbed, to proceed with a search for yet another potential location. He rediscovered—and was very pleased with—a large lawn on the campus of Revelle College.

We shook hands over this new site, relieved to finally settle on one. Now Richard set about thinking through his concept, both spending time on the site and working with with full scale mockups and blueprints his studio in Providence, Rhode Island. He planned to keep the lawn’s open spaces but to define its perimeters with elements formed out of stone blocks based on a simple module. The configurations of these elements would refer to the vocabulary of architecture: posts, lintels, columns, arches, windows, doorways, thresholds. The whole area would become an activated field, its allusions ranging from ancient ruins to a contemporary construction site, with its verticals and horizontals generating complex spatial and historical relationships.

Richard debated the relative merits of different kinds of stone. Granite was hard, and although Richard felt that it perhaps had too finished a look, it was the durable choice. Leaving the surface honed, with traces of the sawcuts, would eliminate any preciousness. A proposal was developed, and the advisory board approved it in January 1983.

Richard began immediately, assembling each arrangement of blocks in his studio using 1:1 scale particleboard blocks built for the purpose of working out the basic masses. Then he and Lane Myer returned to the campus, where we worked with a set of plywood mock-ups, moving them around in various configurations and combinations in order to determine exact locations for all of the elements. It was critical that the work should establish relationships to the existing gradients, perimeters, and trees within this expansive lawn. Human scale, and the ability to orient oneself to the entire space through the experience of each individual element, was always the key. The unplanned adjacencies of the site played an integral role; for example, an old asphalt road remnant passing through one side of the lawn was left unchanged, despite an initial landscape plan that removed it. The work became inseparable from the place in relation to which it had come into being.

Richard chose granite in two colors, a cool Concord Gray and a warm Milford Pink. One senses that these colors could have been selected to reflect the hues of sky and ground, or the gray and brown bark of the area’s large eucalyptus trees. Seventy-one pieces of stone were cut into precisely measured blocks, all with the same end dimensions, and all multiples of 7 5/8”. The exception was a seven-foot-round Brancusi-like table in the site’s northwest corner.

The layout was determined to the fraction of an inch using the plywood mock-ups, and so the foundations for all the stones could be placed in advance. Each element was meticulously plumbed and leveled by Fleischner and a team he had worked with on every project that involved stone, and he examined every placement down to the millimeter.

A tilted sod plane was graded diagonally across the middle of the space. Although barely discernable, this plane, or floor, is integral to the concept of the work, and unites the distant stone arrangements. A place was created: one can’t be in front of, behind, or on top of it. One can only be in it.

The project was completed in time for the graduation ceremony of June 1984. The east elements serve as a focal point and a perfect performance platform or stage for many different events. The main “window” of this grouping frames the trees behind. Lone students can frequently be seen sitting on these stones reading, with sometimes a bicycle propped nearby. Like other works in the Stuart Collection, Richard’s piece has taken on its own life, or lives, in the minds of the students, who have dubbed it “Stonehenge.” Although it has nothing to do with celestial occurrences or the calendar, it freely references ancient and modern precedents with its stark verticals and horizontals, and compels a sense of orientation, measurement, permanence, and place. The project’s real title is simply La Jolla Project.

In the thirty-five years since its installation, this work, encompassing several acres within a rapidly expanding campus, has been the key to preserving one of the university’s last green, passive open spaces. The area south of it has become the Theatre District, including several new buildings, one by architect Antoine Predock, which has been designed to recognize the Fleischner work. The lawn has been chosen for weddings, memorial services, festivals, dances, concerts, and picnics. It is a frequent formal and informal gathering place, and a place for reverie and study. These quiet stones have drawn people in and shaped or influenced many and diverse narratives—from the daily exchanges of academia to the moving drama of ceremony, sanctuary, and remembrance. In a more and more frenetic world, this is one place that lets people decompress, drift, reflect, perceive, and move around without any particular “program” or expectation.

Interview with the Artist

Richard Fleischner

Interview

Joan Simon: Yours is one of the earliest pieces in the collection. I think it’s the third, following Niki de Saint Phalle and Robert Irwin.

Richard Fleischner: I was asked to do a proposal by the committee, and made several trips out. I had originally picked a site that was near the big library, the one that looks like it’s a spaceship, and it was totally in the woods, in a eucalyptus grove. We actually went fairly far on the project. Then on a trip to continue laying the project out, we found the site had already been committed for another university use. After several more trips looking for other sites, I finally fixed on the one that was next to Galbraith Hall. It was a much more open site. These two sites couldn’t have been more different. Although I continue to work with the same set of issues, their hierarchy is subordinate to the givens of the site.

My work is about dimensioned space, and addresses one’s perceptions based on experiencing distinctions within it—placement, form, scale, color, and light. I work with combinations of sculptural markers, plantings, furniture, landscaping, as well as architectural components; and through a dialogue with both the site and the project’s parameters I find the edges, axes, and points from which the rest of the work develops. Considerations for the physical and psychological effect of vistas, borders, pathways, outdoor rooms or defined spaces, seating areas, and their relationship to the natural or built context all influence the way I resolve my sited works. They are integrated into the larger overall context through the definition and articulation of boundaries, site lines, and destinations.

What intrigued me about the site I finally chose, what drew me to it, was that there was already an almost archaeological presence—there were existing markers in the terrain. In the lower area there had been a stage or bandstand. It was a place that had a flattened area, and a kind of edge. There was a very low railing on the back corner: it suggested an architectural corner. I spent a long time looking at that. The trees existed for me as markers as well.

Pretty much the way I work is going from point to point within a site, in a sense almost visualizing myself as the element that might go there. And as all that begins to take dimension, I come up with a scale: you know, it can’t be any smaller than, or any bigger than; this is going to be a point; this is going to be very axial; this is going to be planar. And then, using two-by-fours, or sheets of plywood, I begin to give it some rough dimension.

JS: On the site?

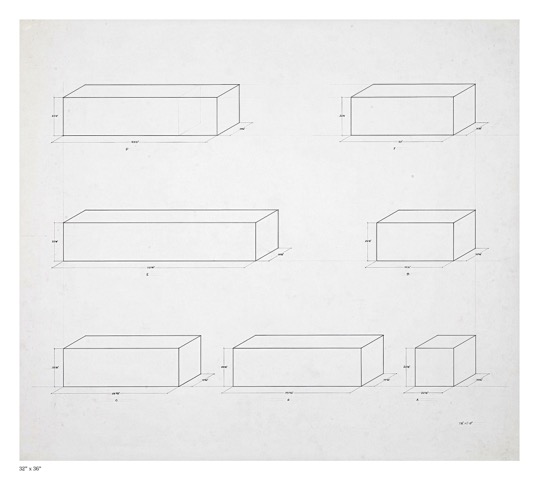

RF: All on site. Then I come back here to the East Coast, to Providence, and I work in the studio full scale on those elements. So the Stuart Collection piece was mocked up full scale in these particleboard blocks. At the time I did several projects that had a modular block construction.1 I was doing a lot with these blocks.

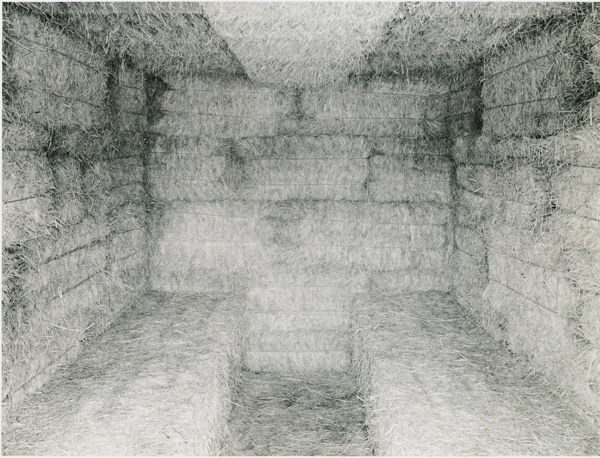

JS: There’s a photograph in your studio showing the modular blocks that goes back to I think 1980. Working with the blocks followed on from earlier working more typically with grass or hay—with organic materials.

RF: Yes. The hay was blocks or bales of hay. When I did Hay Interior, in ’71, a bale of hay was a buck. So for $300 I had 300 bales of hay. That’s a lot of blocks. And with one assistant who was working with me, we would retie them. For Hay Interior—

JS: —which is based on a belowground room-sized tomb, one of those at the ancient Etruscan necropolis Cerveteri, near Rome—

RF: —we built the beams out of hay bales. When my children were really little I was playing a lot with them, and they had blocks. So I made a substantial, heavy set of blocks, like children’s wooden blocks made to a big scale. In the blocks I used for the Stuart Collection piece, the biggest ones were something like ten feet long. A lot of the concept came from Froebel’s blocks, which Frank Lloyd Wright used to play with as a child: they were German, and a sequence of gifts for children that with each set got more and more complicated. It started with a basic cube, then a cube cut into four cubes or into two rectangles, and then more complex, with the pieces getting more numerous and smaller. Later it got into spheres and triangles.

JS: How do these relate to the Stuart Collection project?

RF: I had all these blocks and, on some levels, I was looking for ways to use them. I would never be so literal again.

JS: I think you used something like seventy stone blocks for the Stuart Collection piece. You seem here to be dealing specifically with post and lintel, column and passage.

RF: That was what I was really interested in. It became a ruin.

JS: A ruin that is used in a very vital way.

RF: The fact that it’s used is great—the fact that it’s inhabited, and there are events there. That’s funny and nice.

JS: Part of the reason the piece seems so architectural is that it is furnished as well as framed.

RF: That’s a good expression, “Furnished as well as framed.” That’s excellent.

JS: Your piece is particularly hard to photograph.

RF: My intent was for the piece to be experiential. What I mean by that is, I was taking what I thought were the major gestures of the area that I was working in and amplifying them. There was the lower stage or bandstand area, a flat rectangular plane coming out of the slope of the larger landscape. Working with the blocks, I built a vertical backdrop perpendicular to the bandstand plane at its back edge. The next group of stones was an attempt to reinforce a boundary parallel to and across the site from Galbraith Hall. Third was the round table, which basically becomes a point rather than a plane, but it’s corner-like. It’s almost a stake. The fourth element was a large recessed plane cut into the lay of the land.

I regret not making that sod plane more visible. I did it so subtly that it’s invisible [laughter]. My idea that it was to be like a sunken plane literally derived from a Bedouin man I came across in Jordan. He lived on the site of an olive orchard that he took care of, and all of the parts of his life were quietly laid into this orchard. Where he slept, he’d taken a broom and really just swept out the stones, and tried in the subtlest way to put what read as a flat level plane into this hill. In reality it was neither flat nor level, but its subtle contrast to the existing topography when the light hit it in a certain way was beautiful. It was just quite something.

JS: Do you primarily now work on public commissions? And do you also make studio works?

RF: I’ve always done a lot of gouaches and drawings; I’ve also always done photography. Right now I’m working more in gouaches and photography. A year ago I was in Kosovo for five weeks, photographing and working on issues of the simplest elements that define home. I was very much along the lines of what we were talking about [the Bedouin]; what are the special gestures that focus home life? They are more visible in areas of total upheaval. It’s trying to see the human dimensioning and refining of things on the basis of how we physically relate to things in the body politic, and so forth. And it’s really the lines on which I want to work more. I no longer think the only way to make these things accessible is through large-scale public commissions. All of my work is about acting on, for, and in reply to a site. It’s about perceiving, then acknowledging, then demonstrating an understanding.

None of this is really new. Historically it goes back to Bernini and then to the Greeks and Romans and Egyptians. In my mind, it wasn’t that any of us who were making these public commissions were introducing any revolutionary ideas. But there seemed to be an opportunity to work pretty uncompromised.

I’m interested in vernacular architecture, which is so connected to its source intellectually and emotionally. It’s not overly cerebral. I’m interested in something simple and elegant, not a spectacle. A lot of big projects, and what one goes through to get them realized, don’t allow those passions. I would agree with John Hockenberry, who wrote, “If design is the act of defying forces of conformity, then the elemental gestures of the world’s refugees to defy forces of international chaos, traumatized people in living spaces, are a fitting component of the decade’s design legacy.”

JS: How does this relate to what you are trying to do with the photographs?

RF: What I’m trying to do in the photographs is find any workable situation that right now reinforces these ideas, given the nature of everything else that’s going on —the pressure to compromise, and the lack of reasonable sensibility either in the name of expedience or of art, or cost or time. These are the issues that become my issues. I’ll read you one other quote, by Ezra Pound. He wrote his in 1921:

But if we are ever to have a bearable sculpture or architecture it might be well for young sculptors to start with some such effort at perfection rather than with the idea of a new Laocöon or a triumph of labor over commerce. This suggestion is mine and I hope it will never fall under the eye of Brancusi but then Brancusi can spend most of his time in his own studio surrounded by the calm of his own creations whereas the author of this imperfect exposure is compelled to move about a world full of junk shops, a world full of more than idiotic ornamentations, a world where pictures are made for museums, where no man has a front door that he can bear to look at let alone he can contemplate with reasonable pleasure, where the average house is each year made more hideous, and where the sense of form which ought to be as general as the sense of refreshment after a bath, or the pleasure of liquid after a drought, or any other clear animal pleasure is the rare possession of an intellectual aristocracy.

Quite a quote, huh?