Michael Asher

Untitled (1991)

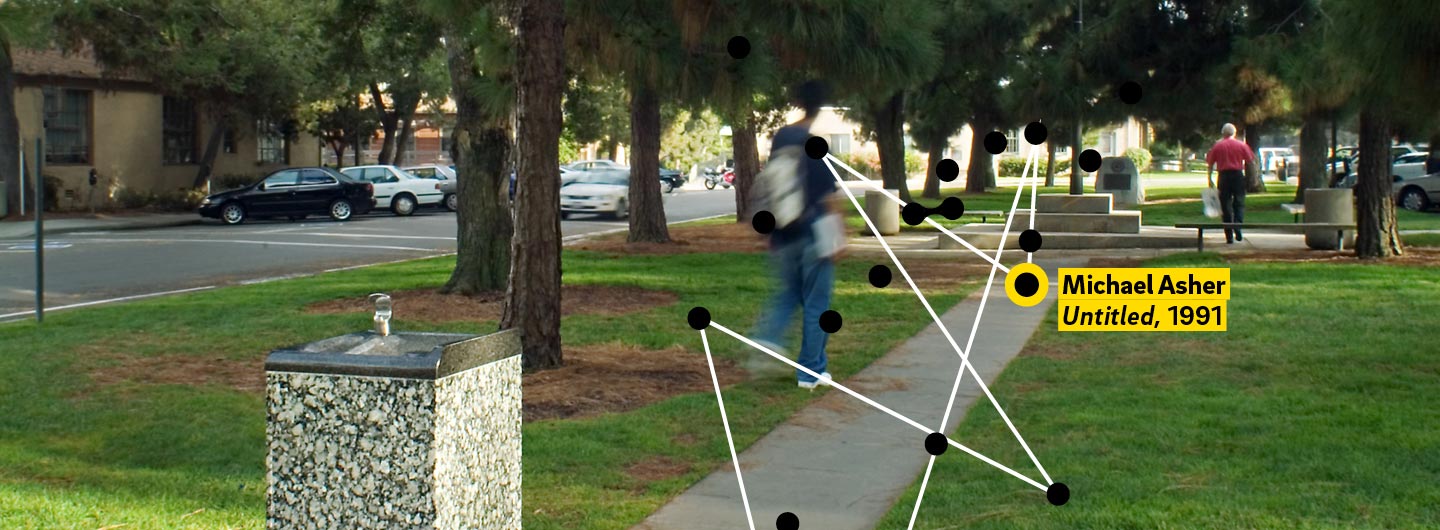

Location: Town Square, near Chancellor's Complex

Audio Tour

About the Artist

About the Sculpture

Although Asher was a seminal figure in Los Angeles and has been widely recognized in Europe, his untitled project for the Stuart Collection is his only permanent public outdoor work in the United States. This functional, polished, granite drinking fountain is an exact replica in granite of commercial metal fountains typically found in schools, business offices and government buildings. Instead of its usual context as interior office furniture, the fountain is placed monument-like on a grass island in the center of Town Square next to the university administration offices and the Price Center. The siting of his work is fundamental to its meaning; it is counter posed with a tall American flag and a granite marker commemorating Camp Matthews, a World War II training center and artillery and rifle range which occupied the land on which UCSD now stands.

Asher's work projects several cultural references into one modest object, and it is a play on sculpture's historic role as representation. When one leans down to drink from the fountain and looks west, the flagpole serves as a line to a rock with a plaque denoting the history of this place. As an ironically monumentalized fragment of any banal administrative environment, the drinking fountain mirrors the nearby monument to Camp Matthews, suggesting both contradiction and continuity between the institutions of defense and of learning, of the military and the university. The fountain, in its modesty and its reversal of the traditional grandeur of water fountains as public monuments, also calls to mind Southern California's need to manage and preserve its natural resources in light of the ongoing water crisis caused by large-scale agricultural and urban development.

Essay

Michael Asher, Untitled, 1991

For Michael Asher, context is all. His work comments on function and often-invisible systems. One of the leading conceptual artists, based in Los Angeles but showing mostly in Europe, he points to architecture and institutional procedures or systems that influence our understanding of things without our necessarily being particularly aware of them. His work is fused with and comments on its setting, sensitizing us to its history. The UC San Diego campus, with its beginnings as a military training ground, seemed a perfect place for him to explore and consider. Although highly recognized and often commissioned for exhibition projects, he had no permanent public work in this country, which was surprising given the recent focus on place, history, and dependence on site. He was high on the Stuart Collection Advisory Board’s list and responded enthusiastically when we called.

Michael first visited the university in 1984. On an extensive tour, two things sparked his interest: the campus signage, which was in great need of clarity; and the possibility of turning a small yellow-brick building near the Gilman entrance into a visitors’ information center. The building, once an electrical switching station, was unused and neglected. Upon reflection and inquiry, Michael decided that the size and complexity of the campus signage made it a less attractive challenge. He abandoned that pursuit. His interest in graphics, however, became an opportunity: in addition to developing a project, he wanted to redesign the Stuart Collection’s stationery—an unusual and typically subversive idea. We use a version of his design to this day.

In the meantime the yellow-brick building was slated for destruction to make way for the new Cellular and Molecular Medicine Facility—development winning out over history. He did not give up, and returned many times over the next four years. Of all the artists who have been commissioned, Michael spent the most time by far exploring, researching, analyzing, and understanding the physical and historic campus. He considered and thought through many interventions. On an extended visit in 1988 he focused in on a site near the chancellor’s office that he felt could be essential to an understanding of the university as both a place and an institution existing within a history.

This area is a median strip about 300 feet long and 55 feet wide, a grassy island surrounded by a parking loop. In the center is a high flagpole that flies the American flag and, on the south end, a stone landmark, placed in 1964, with metal plaques commemorating the training of “over a million Marines and other shooters” that took place here, and the transfer of the land from the military to the university “for the pursuit of higher education.” From 1917 to 1964 the land that the campus occupies had been Camp Matthews, a military training center and rifle range. The flag at the center stood on a concrete pedestal with its date of construction scratched faintly into the original concrete: 1/7/1942. Yet the site was asymmetrical, with nothing to balance the stone marker at one end. To Michael, it was like an invitation.

Michael would add a drinking fountain, a representation in granite of the familiar, institutional, steel drinking fountain used widely in offices, factories, and schools. He proceeded with development and drawings, sending a long, detailed written proposal, as conceptual as it was specific, as philosophical as it was revealing of the social, environmental, political, and economic history of the site. Reviewing the proposal at a meeting in January 1989, the advisory board was very enthusiastic. Certain members of the Campus Community Planning Committee, however, voiced serious concerns, despite the fact that, rather than any evaluation of the art itself, only consideration of the site was within their scope. There was support for the idea of a work of art in this central location, but not for this small drinking fountain. Those in opposition claimed that an identification sign would be necessary for most people to recognize a granite-clad drinking fountain as art. Even then, they said, most wouldn’t believe it. This was the “epitome of a bad idea.” There was vigorous protest, most of which arrived in the form of a letter.

We worked on a response, which stated in part:

As you have probably noticed, many of the Stuart Collection works are not clearly and immediately recognizable as art…this is part of their intention. The notion that art is a part of life and about the act of thinking rather than memorializing, or of being identified as art, is essential to aesthetic development in the 20th century, and it is one of the strengths of the Visual Arts faculty here at UCSD. We think this is an important aspect of the collection and a part of the reason for its placement throughout the campus rather than being confined to a “garden” area, where one’s expectations would be different.

The purpose of the Stuart Collection is not “tasteful design” or cosmetic beauty, but thoughtful composition and integration with surroundings (among other considerations). We are not for a moment proposing that Asher’s fountain “become the central expression of artistic values on this campus, the symbol of UCSD.” Asher’s work does represent tradition, culture, education and research, but it does not announce itself as Art. It acknowledges and includes its surrounds. It has many levels of meaning that can be discovered with some effort. Although one looks toward the flag when actually drinking, this granite drinking fountain has nothing to do with “bowing one’s head” to the flag; indeed, it places itself in opposition to ideas of monumentality and nationalism. We hope that you will present

this work to your colleagues and students in this light rather than as “the central artistic symbol of UCSD.”

Although the Stuart Collection is meant to be an educational tool, individual works do not necessarily promote the virtues of education or of institutions of education. One might compare them to books in the library, in

that we hope to have a significant range of ideas represented.

The project went forward.

Michael proceeded with exceptional deliberation and care. We built a wood model. He worked for days over many samples of granite. The base of the fountain and the top were to be of two different colors: the top, which is stainless steel or chrome in the office-equipment model, would be darker; the base, which is often painted a light brown in office models, would be lighter. Considering disability modifications, Michael slightly lowered the height of the fountain, and adjusted the placement of the bubbler and the button.

The granite parts of the fountain were fabricated to exact specifications at Cold Spring Granite in Minnesota, and the assembly was done by the machine shop at UC San Diego’s Scripps Institution of Oceanography, which fabricates specialized equipment for oceanographic and atmospheric experiments. A revision of the walkway was installed to mirror the space, linking the fountain to the flagpole and the granite marker on the opposite side. The fountain was installed in December of 1991. It became a wonderfully elegant yet low-key addition to a rather ordinary site. It undoubtedly has an air of mystery.

When one is drinking from the fountain, one’s body is aligned in an evenly balanced arrangement made out of the triad of the fountain, the flagpole, and the stone commemorating the military history of the place. Remembering that this was once a shooting range, one might imagine the flagpole as a sight aiming one’s vision on the monument, so that the work perhaps makes reference to the connections that still exist between the university and the military. The work is the opposite of monumental in scale, and yet it is made of granite. It is a representation—a sculpture of a fountain—and a useful object at the same time. Rather than wasting water, as many decorative fountains do, it provides sustenance. Whether as fountain or art, it asks us to question how we use our human, institutional, and natural resources. This water is cooled and filtered.

Before the opening celebration, Michael seemed happily awed by the completed project; he said it made him a little weak in the knees. He gave a talk and slide show about his work and the opening followed. TV news reporters along with some reviewers and academics ridiculed the art, an easy target for them. But the fountain quietly stands and resists its critics, while having many admirers, not to mention frequent imbibers of a refreshing sip of water. Although it does not announce itself as art, it is mysterious enough to have been discovered by students, who, calling it “smart water,” have instituted a legend about its secret powers, and often come to drink before an exam—and perhaps to think about why it’s there. In the geographic and historic center of a campus that grows exponentially every year, this quiet work along with its component elements convey the history of the whole place. Rather than explaining itself, it asks us all to look more carefully—to pay attention.

Interview

Interview with Michael Asher and Joan Simon

Joan Simon: Why did you pick this site?

Michael Asher: Let’s see if I can answer this very clearly. It wasn’t that I had an object in mind that I wanted to install, but there was a problem, or problems plural, that I could perhaps describe, at this particular point. One of the most significant was to produce comparative relations—that I use to learn by, as well as utilize quite often in my own work and in teaching.

JS: In picking a site, you kept looking for something that had the potential for you to trigger this thinking. I know you went to the campus many times.

MA: My notes start with that, because I just had the hardest time finding anything that would function for this logic. Finding a site became almost impossible, compared to projects prior to and after this artwork, where the specific site is designated and the problem is defined from that point. This way of working returned when I finally found the place where the artwork would be placed.

JS: What was it that crystallized for you that you did have some ideas, and the correct site in which to work them? The place you chose has and, I assume, already had in place the memorial marker, the boulder.

MA: That was perhaps one of the key reasons. The plaque on the boulder explained how the area was once a shooting range for the marines and then was deeded to the university.

JS: Why don’t you talk about encountering that for the first time, and what your response was?

MA: There was a parkway with a road around it. On the grass, there was just a path, a flagpole with benches, and a rock monument from the marines. If you looked at it just visually and formally, it was fascinating, because it was structured to be symmetrical but the symmetry wasn’t complete, since nothing balanced the memorial. It also appeared to be designed to symbolically give the visitor a sense of stability. This was likely due to the offices that were represented on the parkway.

JS: Then how did you begin to address what the problem would be, and what your intervention would be? You did alter the site, adding something to it, but passersby may not necessarily realize this.

MA: I wanted to complete the symmetry, in order to produce questions about preexisting elements. I noted, “I didn’t want the object to have the presence of a new marker which must first be identified as part of an autonomous practice.” I thought that idea of the autonomous practice could come later. I wanted to offer some sort of contradistinction to the other projects in the Stuart Collection.

JS: Maybe you should read me the first of your notes, so that I have a sense of how you make them.

MA: One was, “I made intermittent trips from LA to San Diego over a period of X number of years.” Number two, “For the longest time I thought an idea would be impossible.”

JS: And number three?

MA: “I wanted to bring together ideas and objects that were very familiar.” That becomes a problem that I had in general with most outdoor sculpture; I didn’t want to represent abstract forms that would immediately individuate my work in public space.

JS: The things that were preexisting were the flagpole, which you didn’t change—

MA: Not at all.

JS: —and the boulder, and you didn’t change that either. The boulder commemorated Camp Matthews, which was a World War II training center, a rifle range.

MA: I can read you what [the plaque on the boulder] says: “The United States Marine Corps occupied this site known as Camp Calvin B. Matthews from 1917 to 1964. Over a million marines and other shooters received their rifle marksmanship training here. This site was deeded to the University at San Diego on the 6th of October 1964 for the pursuit of higher education.”

JS: That’s a lot packed into one plaque on one rock.

MA: It’s quite incredible, and I mention this point also in my notes. One of the things that one can’t help think of is the military research that might be going on at the university.

JS: The dates of the camp seem to be from the end of World War I—actually from the beginning, I think, of US involvement, in 1917—to the Vietnam War era.

MA: Perhaps the Marines deeded the land because they knew it would be more beneficial to them as a research facility to which they would have access.

I’ll go on with my fifth point: “The project that I finally decided on and was accepted was the installation of a granite water cooler on a parkway where students could traverse or remain and meet other students.” Then my sixth point is, “The parkway was like an island, defined by a road which turned around it, and parking places which met its curb.” The seventh point is, “The trees and grass in it were similar to the trees and grass on the surrounding campus.” Going on to number eight, “What made the parkway different was that, rather than having any building on it, it had been dedicated to what one might call a historical/patriotic function.” And then number nine: “In the center was a flagpole with the American flag with benches around it. South of the flagpole, and close to the end, is a large granite boulder with a bronze plaque fixed to it, which faces the flagpole. And on the plaque is inscribed the following”—and that’s what I read to you.

JS: Before you did your piece, what was on the opposite side of the flagpole?

MA: Nothing but that walkway, which went all the way lengthwise through the middle of the parkway. Otherwise it was just grass and trees.

JS: So you made the pairing complete.

MA: The symmetrical connection, yeah [laughter].

JS: Why a water fountain?

MA: It’s a tool, like I say, for comparisons. “An equal distance north of the flagpole is where I installed the granite water fountain.” The granite water cooler that I had fabricated is a copy of one of the most popular I could find. I started noting, in industrial and office buildings, what was most popular. It’s one model that I think was designed maybe in the ’50s, maybe the ’60s, and it’s meant to be placed up against a wall. Oddly enough, the one that I had produced doesn’t usually go in the middle of a space.

Anyway, I go on to say that “the precise likeness of the granite cooler to the original manufactured one was a good measure of the care that Mathieu Gregoire had been taking in the production of my project.” And I mention him because all the way along, he was just so careful, and would not compromise on anything. And I really appreciated working with him. I go on, “The cooler had a pump so it could be used for drinking.” And then number fourteen, “Additionally, a pump filter and refrigeration unit were purchased from the company that manufactured this model and placed into the unit.” Then number fifteen: “The granite monument, the flagpole and the water cooler,” as I already mentioned, “are all situated on the center of the one path which goes lengthwise through the parkway.” And I don’t know if this is particularly important, but when you take a drink of water the flagpole bisects the plaque as if it were in the sight of a gun.

JS: When visitors lean to take a drink, they get a glimpse of the pole as if it were the vertical line in the crosshairs of a gun sight?

MA: Viewers are not using any sort of mechanical device in front of their eyes to line up anything other than what was there.

OK, so I go on more directly to your question: “Due to producing an artwork for a school setting, I wanted to demonstrate one of the most fundamental tools to my own learning and that was an object and the way of experiencing which could be then used for comparative thought.” Then I go on, taking the most superficial characteristics first: “Visually the granite monument is rough, and its large size makes it immobile, while the cooler is highly polished.” “It had to be assembled from separate parts. It was light enough to be handled.” “The cooler is designed to code so it can be used as any object for architectural installation while the granite boulder is rather arbitrary and could have been any number of sizes, while its presence is massive and overwhelming to the viewer.”

Then twenty, “The design of the cooler is a copy of one which has been infinitely reproduced. For the boulder, it is impossible to conceive that another like it exists.” “The cooler was designed to meet a very specific necessity. The rock was selected due to someone’s taste.” I go on to say, twenty-two, “The boulder is to remind us not only of the legacy, the connection to land had with helping the war effort, but also can’t help [but] remind us of the campus and its involvement in defense research.” And twenty-three, “Hopefully the cooler underscores the campus as a resource tool for those who are interested in education and humanity.” I go on to say that some of the questioning turns around how we use our resources, both human and natural, and what’s at stake.

JS: There are two pieces of yours that I’ve always wanted to ask you about. One of them was at the Clocktower in New York over twenty years ago—you took the windows out. For me it was extraordinary. It was in one sense such a simple gesture and yet so complicated, and it made the space so full and clear. That was part of a body of work that you were doing in the ’70s.

MA: Yes, 1976.

JS: How were those interventions different, if they were, from these later ones? In some ways it was working with the same vocabulary that you still use to amplify a structure.

MA: Generally speaking, the later ones take on more political and social questions than the earlier interventions. They are structured more as a tool with which the viewing public can work on the problems I am describing or outlining.

JS: It seems in many ways you keep returning to the revelation of systems specific to a structure, an institution.

MA: Yes, I’m still very much involved in that—for instance in The Museum of Modern Art work I did on listing the deaccessions.

JS: That was the second of the pieces I was going to ask you about.

MA: It’s the same thing, just in a different way. The collection of the Modern represents the canon of modernism that I had come to understand in school. I assumed that everything they brought in was very specific to that canon, and they would never want to get rid of anything. On the other hand, when I started to learn more about The Museum of Modern Art, I came across an article about something they might have gotten rid of. At some point I began to realize that the objects that were treasures were also quite transferable. The catalogue is left as a list for the viewer to further inquire about what changes take place once the deaccessions are made.

JS: What about the flip side of that, the idea of making something that’s rock permanent—of making an outdoor sculpture? The Stuart Collection piece was your first of these in the United States.

MA: You’re right. It is granite, a traditional material. I decided to go all the way and see if the same material could operate in completely the opposite way from the original monument, and could this become a tool to reevaluate how the representations of different institutions are displayed in public.

JS: It was pointed out to me while I was on campus—I’m not sure I would have noticed on my own—that there is a “signature” of sorts, or at least a plaque, identifying your work. But it’s ankle high, on the curbstone.

MA: Well, I did want to take responsibility for it. I didn’t want it to be totally anonymous. I wanted to account for the fact that it would be on the Stuart Collection map and that it was a work of art. Similarly, I wanted there to be a person’s intent clearly registered behind my artwork, rather than having an institutional origin as the other marker on the parkway. I think if our artworks were truly public and the community helped conceive and fabricate our projects, there would be no need to claim authorship. On the other hand, you might want to ask how we can claim authorship when most of our ideas for artworks come from the public domain.

JS: And why, to play devil’s advocate, shouldn’t the author of a work of art be in the foreground?

MA: I think he or she should. Absolutely. It’s just in this particular situation, where one is almost involved in making monuments—not monuments, these markers, which are part of autonomous production—I would prefer that that be secondary.