John Luther Adams

The Wind Garden (2017)

Location: Near Mandell Weiss Theater, Theater District

Audio Tour

About the Artist

John Luther Adams is a composer whose life and work are deeply rooted in the natural world. The New Yorker’s Alex Ross calls him, “one of the most original musical thinkers of the new century.” Adams studied composition with James Tenney at the California Institute of the Arts. In the mid-1970s he became active in the campaign for the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, and subsequently served as executive director of the Northern Alaska Environmental Center.

Adams was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for Music and a Grammy Award for his symphonic work Become Ocean. Columbia University honored Adams with the William Schuman Award for Lifetime Achievement. A recipient of the Heinz Award for his contributions to raising environmental awareness, Adams was honored with the Nemmers Prize from Northwestern University “for melding the physical and musical worlds into a unique artistic vision that transcends stylistic boundaries.”

Adams has taught at Harvard University, the Oberlin Conservatory, Bennington College, and the University of Alaska. He has also served as composer in residence with the Anchorage Symphony, Anchorage Opera, Fairbanks Symphony, Arctic Chamber Orchestra, the Alaska Public Radio Network and UC San Diego. His music is recorded on Cantaloupe, Cold Blue, New World, Mode, and New Albion, and his books are published by Wesleyan University Press.

About the Installation

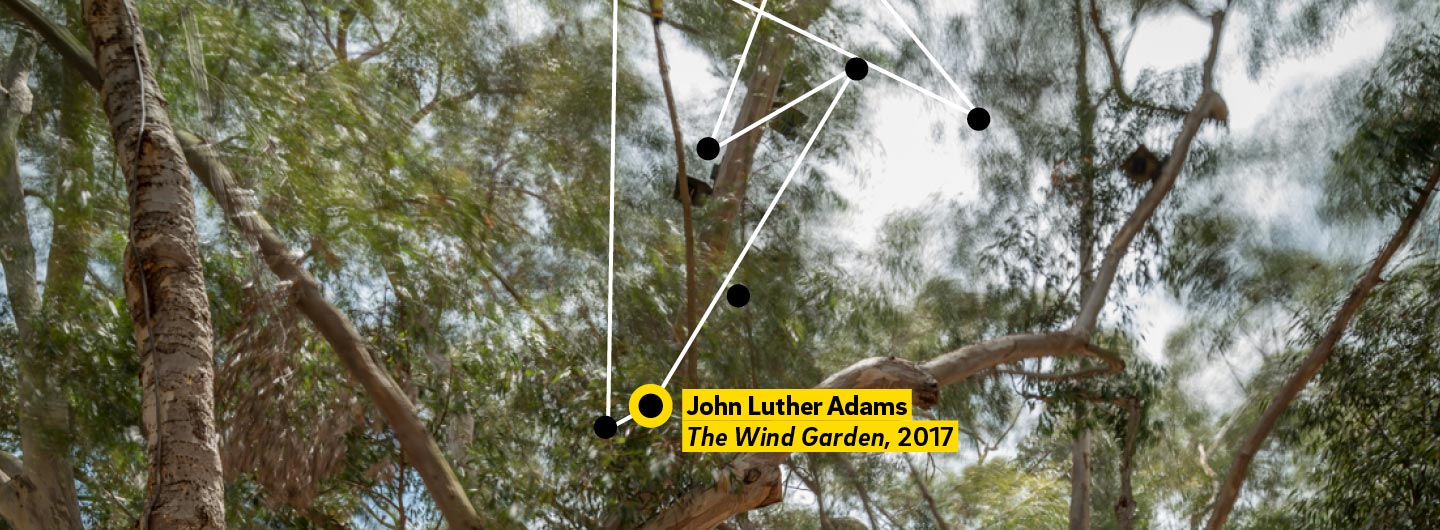

For the Stuart Collection at the UC San Diego, Adams created a musical composition with and within the signature landscape of the campus: the eucalyptus grove. Located in the UCSD Theater District, The Wind Garden invites us to listen more deeply to the music of this place.

There are no pre-recorded elements, no data streams or sounding elements transposed from other locations. Everything that occurs in The Wind Garden is driven by the wind and the light conditions on the site, in real time. This work never repeats itself. Even for people who experience it on a regular basis, each encounter with The Wind Garden is a unique experience of listening and discovery.

Entering along the central pathway, one becomes aware of a soft atmosphere of sound wafting through the grove. The sounds are vaguely reminiscent of bells, voices and strings. But the movement of the trees, leaves and air in the grove makes it difficult to say exactly where they emanate.

In midday the sounds are high and bright. At night they are lower and darker. On overcast days all the sounds are more subdued. And the sounds of summer are generally brighter than the sounds of winter. Throughout the day and throughout the year at every moment the sounds in the grove seem to rise and fall with the wind. Hidden in the trees are 32 small loudspeakers. Attached to the highest branches are 32 accelerometers that measure the movements of the trees in the wind. As the velocity of the wind changes so does the amplitude of the sound.

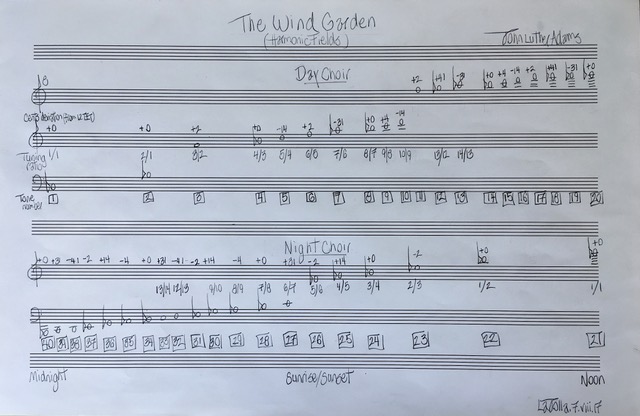

The musical foundation of The Wind Garden is two “choirs” of virtual voices – a “day choir” tuned to the natural harmonic series, and a “night choir” tuned to the sub-harmonic series. As darkness grows deeper, the sounds of the Night Choir fall in pitch and become darker. As daylight returns and darkness recedes, the sounds of the Night Choir rise and fade away. In early morning and again around sunset, both the Day Choir and Night Choir are equally present – producing especially rich harmonic colors. The rising and falling of these choirs traces the contours of the sun’s movement above, below and around the horizon over the course of the year.

Essay

John Luther Adams, The Wind Garden, 2017

John Luther Adams is a composer whose life and work are deeply rooted in the natural world. He studied with James Tenney at the California Institute of the Arts and was deeply influenced by Lou Harrison and John Cage, among many others. In the mid-1970s he became active in the successful campaign for the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, and subsequently served as executive director of the Northern Alaska Environmental Center, before turning his focus entirely toward music.

The 2007 season of the La Jolla Symphony under its new musical director Steven Schick opened its first performance with John Luther Adams’s The Light That Fills the World, and we had never heard a symphony orchestra sound anything like it. It was like the forces of nature had entered the concert hall. While a number of contemporary artists have worked with sound, there seemed a division between the art world and contemporary music. It might be adventurous and interesting to work with a true composer—someone not immediately from the visual arts. So in the summer of 2008 we invited John to visit the campus. He arrived in December. Thus began an eight-year process of experimentation and invention that eventually led us to 2017 and The Wind Garden.

John was able to completely open his mind and ears across the entire campus to the possibilities, which were of course endless. He had no interest in a traditional or repeating composition, but rather he wanted to use the phenomena of the places themselves. His ideas were and are completely site determined, and they took time, reflection, and a lot of long walks to germinate. We walked down into the canyons, through eucalyptus groves, and eventually to Revelle Plaza, where he made the first of many proposals. This was June 2009, and the proposal was titled Listening Point La Jolla, an installation involving a stream of water rising and falling with the tides, hydrophones, colored lighting, metal poles, and removal of a historic fountain and flagpole. It did not work out for a variety of reasons.

John returned several times, and his ideas proliferated. In 2011 he proposed an ambitious work in four places extending almost a mile along the north/south spine of the west campus. It included wind organs, a garden for native plants and birds, a grouping of suikinkutsu (Japanese water resonators) and, at the south end around the theatres, instruments suspended among the limbs of eucalyptus trees. While we loved the idea of a work distributed across the campus in this way, Four Soniferous Gardens was met with many bureaucratic and technical challenges, and so John focused his effort on the groves around the theatres.

Throughout this years-long process John was open and alert to the sensory qualities of every location, and he maintained a focus on natural sounds, imagining analog rather than electronic instruments. His next proposal was the Singing Grove, spanning the entire Theatre District and including native plantings, water, birds, and tuned resonating wind instruments in the canopies of the trees. But in the stillness of evening and throughout much of the day, it became clear that often there would be almost no sound at all, and the work seemed to evaporate into an ephemeral, if beautiful, silence. We wanted something more evident of John’s “hand.” He ultimately agreed to abandon the analog in favor of electronic instruments, driven by natural events, and there began the last chapter of this adventure.

The Wind Garden brought the involvement of Jem Altieri, a brilliant computer music specialist who had worked with John on The Place Where You Go to Listen (2004–2006) in Alaska, and Douglas Alden, an engineer at the Hydraulics Lab at Scripps Institution of Oceanography, along with a UC San Diego music MFA, in sound, Splash Yang, who became technical director. These three worked brilliantly together and as a team for John’s vision. Initially, the source information came from weather stations capable of measuring many parameters—wind, humidity, atmospheric pressure, etc. The first design included 128 speakers, all on different channels, distributed across the entire area surrounding the theatres.

John made an extended visit in June of 2015, and we installed a full-scale mock-up with sixteen speakers in a part of the eucalyptus grove. Many configurations were tried, and as John worked all of his decisions went toward simplicity and elegance. The sensors became accelerometers, small devices mounted high up in the smaller limbs of the trees that measure only movement—clearly, a function of the trees responding to the wind. The trees effectively became their own instruments. This partial and temporary installation of the work became a first, live demonstration that everyone could experience in real time. We celebrated with a big dinner for the Friends of the Stuart Collection, where John and the chancellor spoke.

The permanent installation took place in 2016, and there began extensive tuning of the work. In midday the sounds are high and bright. At night they are lower and darker. The tones of summer are generally brighter than those of winter. Throughout the day and throughout the year at every moment the sounds in the grove seem to rise and fall with the wind. As the velocity of the wind changes, so does the amplitude of the sound, measured by what had now become thirty-two wireless accelerometers, played through thirty-two small, high-definition Meyer outdoor speakers mounted far up in the trees. Natural movement of the tree limbs becomes harmonic sound through the interface of the Max/MSP patch, based on a visual programming language originally developed by UC San Diego music professor Miller Puckette. This complex work was done by Jem Altieri, and later by Jason Ponce, another UC San Diego graduate student in music who worked seamlessly with John in making this extraordinary project possible.

Initially, Jem likened the “release” of the work to the vagaries of the wind and the seasons as letting go a “wild animal.” Indeed, in the winter of 2016–17 this wildness was experienced in the one of the wettest and stormiest seasons on record. Fifty-mile-per-hour winds felled a central tree, which necessitated multiple adjustments and equipment replacement. Throughout this tempestuous beginning, Jason and John developed new programming and tunings such that the grove always—even in the stillest night and roughest winds—creates a working harmonic environment that expresses the presence of the place and the moment. The Wind Garden invites one to listen more deeply to the music of this place. There are no prerecorded elements, no data streams or sounding elements transposed from other locations. Everything that occurs in The Wind Garden is driven by the conditions on the site, in real time. It is 24/7/365, and never repeats.

The musical foundation of The Wind Garden is two “choirs” of virtual voices—a “day choir” tuned to the natural harmonic series and a “night choir” tuned to the subharmonic series. Entering along the central pathway, a visitor becomes aware of this soft atmosphere of sound, vaguely reminiscent of bells, voices, and strings. As darkness grows deeper, the sounds of the night choir fall in pitch and become themselves darker. As daylight returns and darkness recedes, the sounds of the night choir rise and fade away. In early morning and again around sunset both choirs are equally present—producing especially rich harmonic colors. The rising and falling of these choirs traces the contours of the earth’s daily movements around the sun over the course of the year, conditioned by the wind as it moves through the grove from moment to moment.

We inaugurated The Wind Garden in August 2017. Many friends and campus personnel came to listen, and many have returned over and over again. Visitors continue to marvel at the Zen-like experience of sitting and listening to this unique confluence of harmonic and ambient sound. The harmonics invite an awareness of everything present at the site, including the noise of traffic, leaves rustling, birds singing, and of other people. It is difficult to leave as one always wonders what is coming next.

Interview with the Artist

The Wind Garden, John Luther Adams and Joan Simon

Joan Simon: Would you like to begin with specifics or general questions?

John Luther Adams: I think I could go either way. Maybe it will ease me into the topic if we start with general questions, although those may be more difficult.

JS: OK. What do you mean by “sonic geography”?

JLA: Well, I’ve got a great answer for that: I don’t know. It was a term I coined for myself many years ago, in Alaska. It must have been the late 1980s or the early ‘90s, and I imagined a site of geography, a region that might exist somewhere between the world itself and our experience of the world, between human imagination and this miraculous planet that we inhabit.

In those days I would have been probably more specific, at least for myself, and talked more specifically about Alaska. But I really didn’t know exactly what I meant by sonic geography. It just had a ring of truth about it. It was kind of an ideal to which I aspired. The concept was tied, in my heart, my mind, and life to a specific geography. But as the years have gone on, the work has led me into broader and broader understanding of what that might mean, what that aspiration is. I think ultimately, it’s about—I am trying to compose home. Like so many of us these days, I grew up here and there and I never really understood what home was until I came to Alaska, and I think all my life I’ve been trying to, through music, through my work as a composer, to feel more fully, more deeply at home in the world.

JS: You’ve spoken about a number of your pieces invoking air, earth, water—

JLA: —and wind.

JS: —and wind. The Wind Garden, on the campus of UC San Diego, is the Stuart Collection’s nineteenth commission. How was the idea to do a piece there proposed to you?

JLA: We dated for so long [laughs]. We looked at so many sites over so many years, I can’t honestly tell you or give you an executive summary of that narrative. All I know was that Mary Beebe and Mathieu Gregoire heard my music at a concert of the La Jolla Symphony, which is conducted by my dear friend Steven Schick, the great percussionist and conductor. I think that’s where it started.

I think Mary and Mathieu must have had some interest in this composer from Alaska and thought maybe we should talk to this guy. I suspect they became aware of The Place Where You Go to Listen, the installation in Alaska, and probably thought something might be possible.

They invited me down, and lord knows how many trips I made back and forth—sometimes when I was coming for a residency with the music department or doing something else on the West Coast, or sometimes when we were on our way to Mexico, where we spend a lot of time, but Mathieu and I walked all over that campus over the course of years looking at I can’t tell you how many sites.

Somewhere along the way we found—and I still chuckle when I hear people say— “the theatre district”—three theatres that form this enclave on the edge of the campus. And I think we zeroed in on four different locations within the theatre district. At one point I was proposing the idea of a piece with several locations—three or even four distinctly different but related pieces.

They had to be patient with my creative process, and I had to be patient with the gauntlet of a major university. It was always some damn thing. I didn’t like the site. Or I liked the site and we hit some institutional obstacle. We just kept looking. It was a long process and then we came to the eucalyptus grove.

JS: Going around for so long, only to come back to the most obvious, distinctive landscape site there—

JLA: —and I am an unrepentant eco-extremist, and I resent what eucalyptus trees have done to the biome, the native vegetation in California, especially in that beautiful haut chaparral coastal zone. Between freeways, sub-divisions, shopping malls, and eucalyptus trees—it’s almost gone.

JS: Why did eucalyptus trees become so ubiquitous?

JLA: Because the railroad brought it in, the way they brought in kudzu. In the southeast United States, they brought in kudzu from Japan to stabilize the banks of the railroad tracks. And then of course it went wild and ate up native trees and plants and houses in the South. You see these old farmsteads that have disappeared under these walls of kudzu. And they did a similar thing in California with the eucalyptus, which they brought in from Australia, where it belongs. Native birds don’t utilize it. It’s just not a friendly environment for native biota.

So I resented eucalyptus and resisted them every step of the way. And of course, they are the quote unquote signature landscape of the UCSD campus. I probably would have, given my druthers, chopped them all down, and filled the place with native vegetation. It would be partly a restoration project, but that wasn’t gonna happen.

Somewhere along the way I had that aha moment when I looked up and I watched the wind blowing through the canopy of those eucalyptus trees. I watched them dancing in the breeze. So I thought, well Mr. Eco-Nazi, you’re not gonna get rid of them. They really are beautiful if you forget what they’ve done and are doing to the environment. They’re gorgeous. So I thought, OK, I’ll embrace them, and I’ll make something. I’ll make beautiful music with them.

JS: How did you start developing the ideas for what the music would be? Did you start with listening, or making notes, or something else? What was the process?

JLA It’s everything all at once. I generally tend to work from some big image or concept and then work deductively or subtractively. I’m a hedgehog, I’m not a fox. The hedgehog does one big thing. So I start with one big idea and work my way through layer upon layer to the specific details. There’s always a bunch of jumping around from layer to layer. I must have started with this idea: OK, this is going to be the wind garden. Look at these trees dancing. I knew I wanted to do something with wind.

The basic concept for The Wind Garden was, OK, I’ve got the cycles of the seasons, I’ve got the movements of the sun, up and down, around the horizon. And then I’ve got the wind. So I’ve got this big cycle of night and day, light and dark, and then I’ve got the moment to moment always changing presence of the wind on the site. What else would I need?

JS: How do you capture all that?

JLA: Well, I compose the landscape, which I’ve been trying to do all my life. It’s what I do. I imagined the musical territory, which is what I do, what I’ve always done. And then, you know, we just, it’s a very easy thing to say, OK, here is where we are, begin with GPS precision. This is where The Wind Garden is. What does the sun do around the site? What are the cycles of night and day and the seasons of the site? That determines the way the harmonies will rise and fall over the course of a year. So it’s the score, you could say, that’s a legitimate way of thinking about it. It’s a musical landscape. But then you’ve got to bring in the singers to breathe life into the landscape, to traverse the landscape, to sing the land, to sing the place into being.

The singers in this case are the trees. Those eucalyptus trees that I had such a chip on my shoulder about. So suddenly they became not only beautiful dancers, but singers. And each one of those singers—thirty-two of them—is an individual. Each one is a soloist. Each one is a tree and a loudspeaker and a motion accelerometer—a motion detector. And so we have these thirty-two different data streams gathered from these individual trees, these individual dancers and singers.

It’s spread out over the site. There’s always something singing. Even if the wind is just barely present. Even if the site is just, just breathing. There’s always some trace of movement. And those are some of my favorite moments in The Wind Garden, which usually occur early in the morning or in the evening, when the wind has fallen almost still and you can hear the breathing of the trees, the site.

JS: Is there something I haven’t asked you about the piece or you think should be recorded that one should know for now or the future?

JLA: A great question. I suppose another thing to throw in, which might be a kind of visual coordinate for people, is the layout.

My music has always been haunted by space as place. For years that was a kind of poetic or metaphorical idea, but more and more in my recent work, physical, geographical, volumetric space—the space that we inhabit—has become a fundamental compositional element.

For this big piece that premiered just last year called Become Desert—a big piece for a symphony orchestra and chorus—the ensemble is like a hundred musicians, but it’s exploded into five different ensembles. The fundamental decision for that piece was not just what the instruments would be, but where they would be located, and I couldn’t start working on the piece until I had the physical space mapped out.

The first time I ever did that was The Wind Garden, so that was a huge breakthrough for me. I was able to do some things that I had tried to do in The Place Where You Go to Listen, but because that installation is in a small indoor space, an enclosed space, it was acoustically impossible for me to do what I wanted to do. But when I went outside, in a larger unenclosed space for The Wind Garden, I tried the same things, things that have to do with tuning and the relationships between the different tones and harmonic fields.

Outside it worked beyond my wildest expectations. And it was just a thrill when I started hearing these thrity-two voices from all these different locations, and hearing from one end of the garden to the other. And being in one location and you could hear things rising and falling all around you and have a sense of where they might be. Although sometimes, you think, wait a minute—is that over there? Or is it in front of me or behind me?

The physical design of the space was perhaps the single most important—and certainly the new—dimension of The Wind Garden for me. It’s sort of my little chapel fantasy because you walk through there and it has the vaulted ceiling. Suddenly I love the eucalyptus trees because they create this lovely, curved ceiling. You walk into the grove and it’s almost like walking into a chapel with a high ceiling.

There are two spaces in the piece. One that I think of as the central aisle, and you can walk through that and keep going and have a lovely passage through the space. Or, you can get two-thirds of the way down the central aisle way and you can take a little left, and walk over into what I think of as the apse. I’m not religious and this is like a one-armed cross, right? You can walk into that one arm of the cross and that’s its own space. It’s a smaller, intimate space and there are three benches in there. It’s intended for people who don’t just want to pass through; it’s for people who want to settle in and have an extended, deeper listening experience.

I think that’s the answer to your question. I wanted to tell you a little bit about the space.